The global sanctions policy has created an intricate web of trade restrictions, often uncoordinated and overlapping, reshaping international trade patterns. This is particularly evident in countries like Russia and Belarus, which have faced an unprecedented level of economic restrictions in recent years. However, sanctions do not always achieve their intended effect and, at times, can be counterproductive. As targeted countries respond with counter-sanctions and develop mechanisms to circumvent trade restrictions, unintended consequences emerge, affecting both the sanctioned states and the global economy.

Belarus provides a striking example of how external trade restrictions initially led to the creation of elaborate sanctions evasion mechanisms, producing outcomes that were often unpredictable. This article explores how export sanctions have been used as a political tool, how Belarus has adapted, and the broader economic implications of this ongoing game of sanctions and countermeasures.

How sanctions are used as a political instrument

The use of economic sanctions as a key foreign policy tool by the West against Belarus was almost inevitable. In today’s geopolitical landscape, trade restrictions have become one of the most effective means of exerting pressure on states, particularly as direct military interventions are increasingly seen as relics of the past.

The specific design of these sanctions reflects the nature of Belarus’ trade relationships. Unsurprisingly, Western restrictions have primarily targeted Belarusian exports of potash fertilizers and petroleum products, two of the country’s most significant economic lifelines.

However, in Belarus’ case, sanctions extend beyond direct export bans and made the country one of the most sanctioned in the world. They have also significantly disrupted the country’s logistics and transport potential. As a landlocked state, Belarus has long served as a vital transit hub for trade between Europe, Russia, and Asia. The country’s infrastructure historically supported key trade flows—from the Baltic to the Black Sea and from Western Europe to Russia. Western sanctions have effectively curtailed Belarus’s ability to capitalize on its strategic location.

But sanctions do not exist in a vacuum; they provoke countermeasures. Over the past few years, Belarus has systematically developed sanctions circumvention mechanisms, not only for its own restricted exports but also for those affecting Russia. Prior to 2022, Belarus often exploited differences in the scope of sanctions imposed on Russia and Belarus to facilitate trade that was restricted for Moscow but still accessible through Minsk. This ability to maneuver between Western trade restrictions provided both economic and political leverage.

The Data and Statistics Problem

Sanctions rely on transparency to measure their effectiveness. This is why sanctioned states have a vested interest in concealing trade data, particularly in areas where they are experiencing difficulties. Belarus, for instance, has restricted access to key foreign trade data, making it difficult to track the real impact of Western sanctions.

However, international trade has a dual-sided nature—the flow of goods must be recorded by both the exporting and importing country. While Belarus may suppress its trade statistics, its trade partners, including the European Union, publish detailed and publicly accessible trade data.

This data discrepancy provides a unique advantage for analysts and policymakers. By examining European trade records, it becomes possible to:

1. Assess the direct impact of sanctions on Belarus’s economy.

2. Identify trade strategies used by both Western and Belarusian actors to navigate restrictions.

3. Determine which sanctions remain effective and which are easily circumvented.

Do Sanctions Work? A Look at the Numbers

A closer look at European and Belarusian trade statistics reveals both the effectiveness and limitations of sanctions.

By 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Belarus’ alignment with Moscow, the European Union significantly reduced imports from Belarus. However, exports from Europe to Belarus did not decline at the same rate—in fact, in some cases, they even increased.

This has created an unusual situation: while Belarus’ trade surplus with Europe has shrunk, the EU’s trade surplus with Belarus has grown. Ironically, European businesses appear to be benefiting from the very sanctions designed to isolate Belarus economically.

Belarus, however, has found ways to extract its own benefits from the situation. Despite restrictions, the country has continued to acquire Western technology and equipment, albeit in a reduced and indirect manner. Moreover, Belarus has become a key player in sanctions circumvention for Russia, particularly for goods that can still legally enter Belarus but are banned from direct export to Russia.

One striking example is the boom in European car exports to Belarus. Since 2022, imports of German, Polish, and Lithuanian vehicles into Belarus have surged by €1–1.5 billion annually—a phenomenon that is difficult to explain without considering that many of these vehicles likely end up in Russia.

To be fair, Belarus is not the only country serving as a transit hub for sanctions circumvention. Many Asian and Caucasian countries have engaged in similar practices with varying degrees of effectiveness. However, the role of Belarus as a critical gateway for sanctioned goods has significantly bolstered its economy—just as it has fueled economic booms in several Russian-bordering states.

A Game of Cat and Mouse

Since 2022, the evolution of sanctions and countermeasures has resembled a game of cat and mouse. Each new round of Western sanctions triggers new strategies for circumvention, prompting further refinements in sanctions enforcement.

Initially, direct exports of many Western goods to Belarus were blocked. However, these goods soon began arriving via alternative trade routes, often through intermediary countries. When secondary sanctions made these re-exports riskier, Belarusian and Russian businesses shifted to using indirect trade mechanisms—sometimes shipping goods under the pretense of export to a third country, only for them to be redirected to Belarus or Russia.

A similar pattern applies to Belarusian exports. Despite restrictions, Belarusian goods continue to find their way onto global markets, often through complex trade networks.

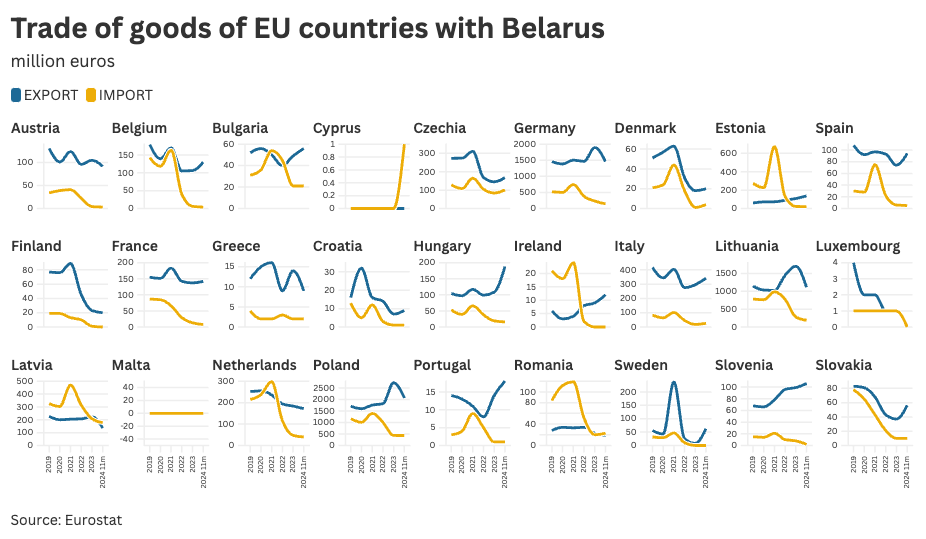

The dynamics of trade in goods between the European Union and Belarus reveal not only significant differences between individual countries but also a stark contrast in the trends of exports and imports as a whole. By 2024, exports from many EU countries to Belarus had, in several cases, surpassed pre-pandemic levels from 2019—a time before the full-scale war in Ukraine in 2022 and the political crisis in Belarus in 2020.

In sharp contrast, imports of Belarusian goods to the EU have plummeted across the entire bloc, with some countries experiencing an almost complete cessation of trade. When comparing figures over equivalent time periods, it becomes evident that while European exports to Belarus have shown resilience and even growth, Belarusian imports into the EU have undergone a dramatic decline, in some cases approaching near-zero levels.

By late 2024, Western policymakers sought to harmonize Belarusian sanctions with Russian ones, aiming to close loopholes that allowed Belarus to act as a backdoor for restricted goods. This, however, will likely trigger yet another cycle of sanctions evasion tactics.

Unintended Consequences of Sanctions Circumvention

While sanctions circumvention has helped Belarus maintain access to key goods, it has also created serious economic risks for the country. Some of these risks are apparent, such as increased logistics costs due to re-routed trade flows, but others are more insidious:

1. The expansion of a shadow economy. The necessity of circumventing sanctions has driven large segments of the Belarusian economy underground, leading to reduced tax revenues and increased use of cash transactions, which weakens economic oversight.

2. An influx of uncontrolled imports. Goods meant for the Russian market increasingly stay in Belarus, undermining local industries. Official data confirms this: in 2024, Belarus’s trade deficit widened to $5.37 billion, compared to $3.3 billion in 2023.

3. Russian businesses exploiting Belarus as a backdoor. With Belarus serving as an entry point for goods restricted in Russia, many Russian businesses have begun to dominate the Belarusian market, eroding the position of local producers.

Conclusion: A Double-Edged Sword

By developing an extensive network for sanctions circumvention, Belarus has gained access to critical goods and created new economic opportunities. However, this has come at a cost: the rise of a shadow economy, an increasing trade deficit, and growing foreign influence over Belarusian markets.

If current trends continue, Belarus’ gray economy will gradually overtake its legitimate sectors, leading to a situation where traditional businesses struggle to compete against firms thriving in a sanctions-bypassing environment.

Ultimately, Belarus’ long-term economic stability depends on a return to transparent and predictable trade practices. Until that happens, the country will remain locked in an endless cycle of sanctions, counter-sanctions, and circumvention tactics—where short-term gains come at the cost of long-term economic uncertainty.

This article was prepared in collaboration with the ForSet Data Communication Fellowship Program.