Minsk has very little room to maneuver in its relations with the West. For the European Union and Belarus’ neighbors, security concerns are paramount. At the same time, the Belarusian regime remains heavily dependent on Moscow. As a result, bargaining over political prisoners has become its only viable channel for engagement with the West. However, Brussels is unwilling to negotiate on Minsk’s terms.

Ruler on the defensive

Judging by indirect signs, Belarusian officials are currently debating the issue of political prisoners.

On July 1, the Belarusian ruler acknowledged that not everyone in his inner circle supports granting pardons. Some unnamed officials have reportedly argued that political prisoners should remain behind bars until they die.

“Is it our goal for them to die there? God forbid, of course,” he said, noting that he would be the one held responsible in such a case.

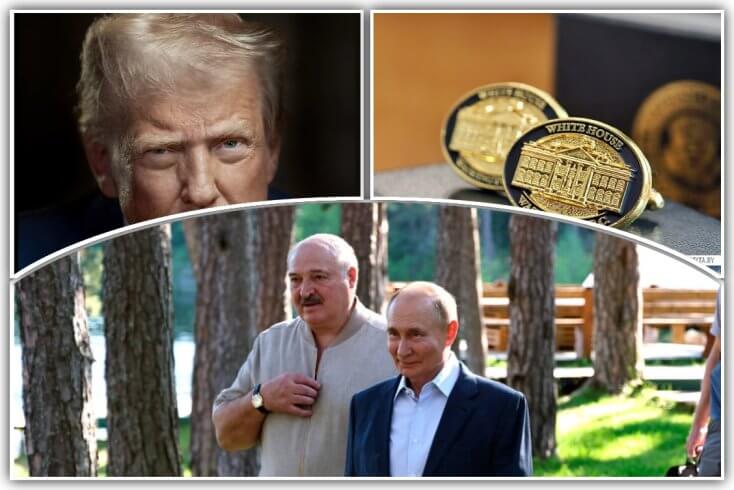

His remarks came two weeks after he pardoned prominent opposition politician Siarhiej Cichanoŭski and 13 others following a meeting with Keith Kellogg, U.S. President Donald Trump’s special envoy for Ukraine, in Minsk on June 21.

Łukašenka revisited the topic on July 31 during a meeting with Belarusian diplomats in Minsk. “Some in our society have begun not just to criticize me, but to raise wild howls… So what? Are we going to keep feeding them here for free, clothe them and so on?… It’s not cheap, after all.”

Who is unhappy with the pardons?

It is likely that the security forces have been alarmed by the pardons, fearing they signal a shift toward political liberalization. In such a scenario, their influence would inevitably decline.

Moreover, security officials might become scapegoats for the excesses of past mass repression campaigns. This is a familiar pattern in autocratic regimes. For example, when Josef Stalin scaled back his terror campaign in 1938, NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov was arrested and executed along with many of his subordinates. Though they had followed Stalin’s orders, they were accused of abuses.

Clearly, Łukašenka cannot ignore the concerns of his security chiefs. The security apparatus is the backbone of his regime. He is attempting to reassure them, urging caution rather than alarm.

At the same time, the ruler is questioning the logic of continuing to keep so many political opponents in prison.

Until recently, the authorities have followed a crude survival instinct—arresting and beating anyone who stood in their way.

But five years have passed. It may be time to reflect. The immediate threat of new protests has been suppressed. The desire for revenge has, at least partially, been satisfied. So what is the point of ongoing repression?

The regime has promoted the recent pardons through Łukašenka’s press service and state media as acts of humanitarianism.

Yet the ruler himself contradicted this narrative. “This is politics,” he said.

And the politics is clear: it’s about trying to strike a deal with the West.

Very limited room for maneuver

At the same meeting with ambassadors, Łukašenka outlined his approach to relations with the West: Belarus is doing everything right and will make no concessions. On the contrary, he insisted, it is the West that must yield. According to him, the West’s strategy of “democratization through sanctions” has failed.

His speech implied that Belarus should wait for new leadership to come to power in EU countries and exploit divisions within Europe regarding Belarus. He encouraged diplomats to engage with foreign businesses, media and think tanks. He also pointed to “Trump’s return” as a “window of opportunity.”

The problem, however, is that Minsk has extremely limited room to maneuver in its dealings with the West.

For EU neighbors, the top concern is security—particularly the presence of Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus, plans to deploy the Oreshnik missile system, the upcoming Zapad-2025 military exercise in September and other aspects of the Kremlin’s growing military footprint in Belarus.

Minsk always has to look over its shoulder toward Moscow before considering any compromise with the West on these matters.

In some areas—such as the use of migrants to pressure neighboring countries—the Belarusian authorities act in coordination with Russia and do not have full autonomy.

But in other areas, especially those involving political prisoners and domestic repression, Moscow does not exert tight control. Here, Łukašenka retains a degree of freedom and sees this as his only bargaining chip with the West.

Forced deportation

In his speech to diplomats, the Belarusian leader openly endorsed the policy of forced deportation for political dissidents.

This is not a new tactic. Authorities have used it since 2020. But now it has been formalized—as a principle and as a condition for release.

At the same meeting with ambassadors, Łukašenka said: “If we release someone, there’s one condition, no matter who’s asking me (mainly the Americans): you want them—take them, deport them.”

This means dissidents now face a stark choice: prison or exile. They may not even be asked for consent. They could be taken from prison with bags over their heads and delivered directly to the border.

EU refuses to negotiate with Łukašenka

For political prisoners to serve as bargaining chips, the other party must be willing to recognize them as such. However, the EU refuses to negotiate with Minsk over political prisoners.

Brussels sees the release of political prisoners as a precondition for negotiations. Minsk, on the other hand, wants the EU to lift its sanctions in exchange for political prisoners. If the prisoners are freed in advance, the regime loses its leverage.

At this point, supply and demand are completely out of sync.