Despite a recent public outcry over arrests of celebrities, reprisals in Belarus continue at a steady pace. The methodical grinding down of dissent scares people no less than unexpected severe attacks.

Arrests of celebrities

On October 31, a judge sentenced the Tor Band members to terms ranging from seven and a half to nine years in prison. The interior ministry last month declared the Telegram channels of writer Andrej Chadanovič and filmmaker Mikałaj Chalezin extremist content. Police briefly detained singer Łarysa Hrybalova, while blogger Ana Bond spent 15 days at the Akrjeścina detention center, human rights defenders reported in early November.

Hrybalova and Bond have not commented on their detention, just said on social media that they were fine.

Law enforcers have probably warned them against publicly criticizing authorities or else they may re-arrested or lose contracts with advertisers and customers in Belarus. Relatives of many political prisoners are afraid to talk to human rights activists for fear that law enforcers will retaliate by making life much worse for their loved ones behind bars, although there is no evidence that silence has actually helped anyone.

Anyway, human rights defenders do not know exactly how many people are arrested on political grounds. Arrests of celebrities make headlines, creating the false impression of a new wave of reprisals, frightening many in Belarus.

Steady pace of reprisals

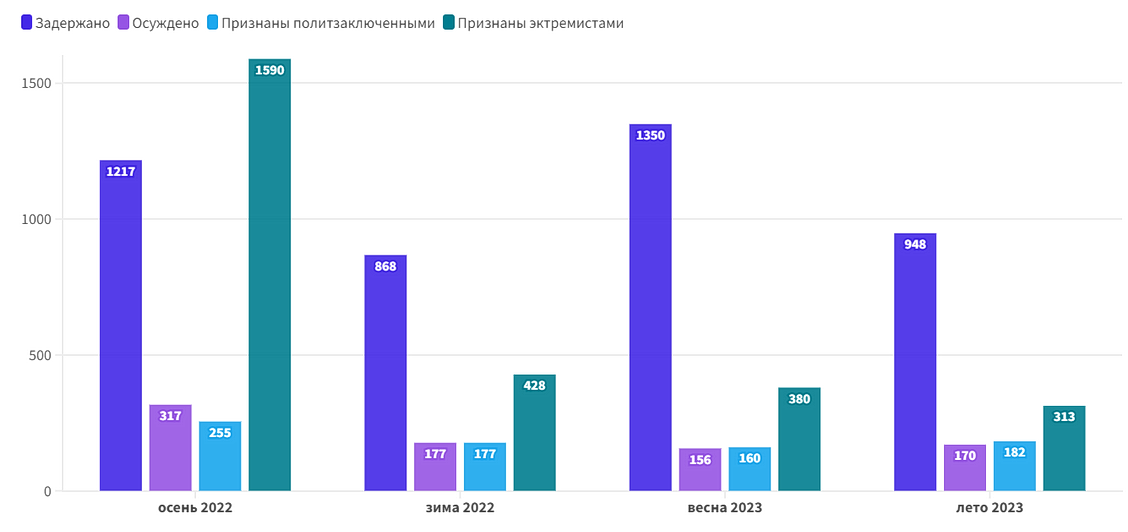

Numbers suggest, however, that political reprisals have reached a plateau. Sociologist Hienadź Koršunaŭ analyzes four indicators: recognized political prisoners, arrests, sentences, and people added to the list of extremists.

In 2023, monthly numbers were close to the average. The repressive machine is working fairly steadily, without sudden spikes or downtime, except for the peaks of arrests in March and June and a drop in all indicators in January and July, the months with many weekends, holidays and vacations.

According to the chart, the indicators in the last three seasons are very similar.

Reprisals from fall of 2022 to summer of 2023

Source: Viasna. Graph: Hienadź Koršunaŭ, Center for New Ideas.

Top legend: arrested, convicted, recognized as political prisoners, declared extremists

Bottom: fall 2022, winder 2022, spring 2023, summer 2023

Civil society organizations

Three years into the political crisis, the regime does not feel victorious enough to loosen the screws, as it has always done in the past after crushing street protests. Having driven the protesters out of the streets, the government has not stopped the crackdown.

Moreover, in spring 2021, Minsk declared war on civil society organizations (CSOs). Alaksandar Łukašenka urged his government “to deal fundamentally” with CSOs, arguing that loyalists were “pointing fingers and already demanding” a purge. Then-Foreign Minister Uładzimir Makiej said that tougher European Union sanctions would lead to the disappearance of civil society in the country.

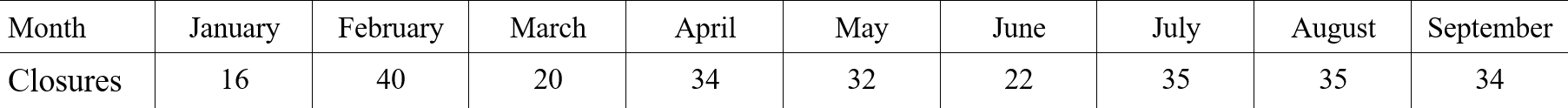

Just like individual reprisals, closures of CSOs also have reached a plateau.

CSO closures in 2023

* Includes both CSOs in the process of forced liquidation and CSOs that decided to close without waiting for a court decision.

Data: author’s calculations, Lawtrend monitoring

An average of about 30 CSOs were shut down per month in 2023. As many as 1,173 were closed from September 2020 to December 2022, or an average of more than 73 per month.

Schedule of arrests

Reprisals mainly depend on the system’s capacity. When protests peaked in 2020, the police and courts worked overtime, setting new records. In the long run, however, any system, especially a bureaucratic one, goes back to a normal and standard schedule without overloads.

Fewer reprisals were reported during New Year’s holidays and summer vacations of court employees and law enforcement officers.

Trials proceed at their normal pace, with no apparent correlation to defendants’ popularity. The repressive machine does not seem to target new opinion leaders, celebrities or social media accounts, which would be politically reasonable, but picks people in a random order. For example, in October, a court recognized as extremist opposition politician Franak Viačorka’s TikTok account, although it had not been updated for more than three years and had just 99 subscribers.

Sophisticated software for dictatorship

The law enforcement agencies have a huge amount of video footage from the 2020 protests: from street CCTV cameras, filmed by security officers, or simply found in gadgets confiscated from journalists or activists. ByPol reported that the law enforcement agencies use Kipod, an intelligent video surveillance software developed by Synesis, a Belarusian IT company. The technology enables them to identify a person with a probability of more than 94 percent.

Synesis denies it, but many protesters have been identified from videos. This summer, Lithuania’s Delfi published Mikałaj Maminaŭ’s documentary “Chronicles of the Present.” Police uses the footage to identify and arrest protest participants.

The software has its limitations. It may take long to process hundreds and thousands of terabytes. It is quite likely that the law enforcement agencies’ computers are processing videos 24/7, automatically recognizing more and more faces of protesters day by day. Some have already been arrested, some have fled abroad, and others will be detained soon.

Everyone is at risk

The government continues systematic political repression, methodically grinding people down. Human lives are behind the average numbers of arrests per month.

Such routine reprisals unsettle those who are still free in Belarus. Even if you have not been arrested yet, you cannot be sure that you will not be arrested tomorrow for taking part in peaceful protests three years ago or reposting a tut.by weather forecast from many years ago because the media outlet was labeled extremist more recently.

Some dissidents who have not yet been arrested are considering emigration. Those based in Belarus are scared and keep the contacts of the Viasna Human Rights Center and BYSOL solidarity group just in case.