On October 24, Alaksandar Łukašenka held a meeting with youth activists. During the 2.5-hour propaganda event the Belarusian ruler was showered with praise, but his personality cult has not taken hold.

“Man who made this country”

The meeting was timed to coincide with the 10th anniversary of Minsk’s Palace of Independence, Łukašenka’s posh office, and brought together activists of the Belarusian National Youth Union (BRSM), Pioneer Organization and some “Komsomol movement veterans.”

Young people are a good audience for sharing wisdom in the genre of nostalgic memories. Łukašenka spoke about his love for nature, his student youth and his personal contribution to architecture, agriculture, automobile engineering, industry and the Hi-Tech Park. He especially emphasized his effort to safeguard Belarus’ independence.

Łukašenka’s press service labeled the gathering a “meeting of generations.”

It was one of a series of PR stunts designed to strengthen the image of Łukašenka as a historic figure, a true national leader and a great helmsman, without whom Belarus’ inhabitants would have suffered under the oppression of the world bourgeoisie.

In the last decade or so, spin doctors launched many campaigns to promote Łukašenka, including a tour for schoolchildren, a merchandise chain and an endowment named after him.

“Path of the First [president]” takes kids to the Mahileŭ region, where Łukašenka grew up, studied and worked, absorbing life experience. “Merch of the First” sells clothes and accessories with Łukašenka’s wisdom, such as “Undress and get down to work.” “Fund of the First” distributes grants to handpicked talents.

On October 8, Juryj Alaksiej, director general of Biełarusfilm, came up with the idea of making a movie about Łukašenka. “This is the man who made this country. This is the man who is leading Belarusians along this very path. We live in unique times,” the head of the film studio said.

Cult of invincible among nomenklatura

Propaganda has glorified Łukašenka for all 29 years of his rule. However, its style and scope changed after the 2020 presidential election, which turned out to be an embarrassment for the Belarusian ruler. Previously, stalwarts promoted the Belarusian strongman among the nomenklatura as invincible. But that image was clouded by his poor showing in the race.

No matter how desperately Natalla Kačanava, chairwoman of the Council of the Republic, praises her leader these days, she is still unlikely to outshine the former Brest region governor, Kanstancin Sumar, who said in 2004 that Łukašenka was “a little higher than God.” Seven years later the governor proposed erecting a monument to Łukašenka’s program of rural revival.

Looking at the poor state of Belarusian villages under Łukašenka, one can understand why he did not give his consent.

In 2007, the Belarusian leader revealed, “It took me a long time to stop all attempts to glorify me. I’ve always said that when I’m no longer president, then you can praise me as much as you want, but it’s not fair to glorify the incumbent.”

He added that in Belarus “you don’t see portraits of the president anywhere except state offices.”

At that time, the shining image of the leader was promoted without particular zeal. In general, state propaganda has been operating at half throttle until 2020.

Although the BRSM was up and running, young people were not strongly forced to join it. Łukašenka’s museum in the village of Aleksandryja, Shkloŭu district, was functioning, but no mass pilgrimages were organized there.

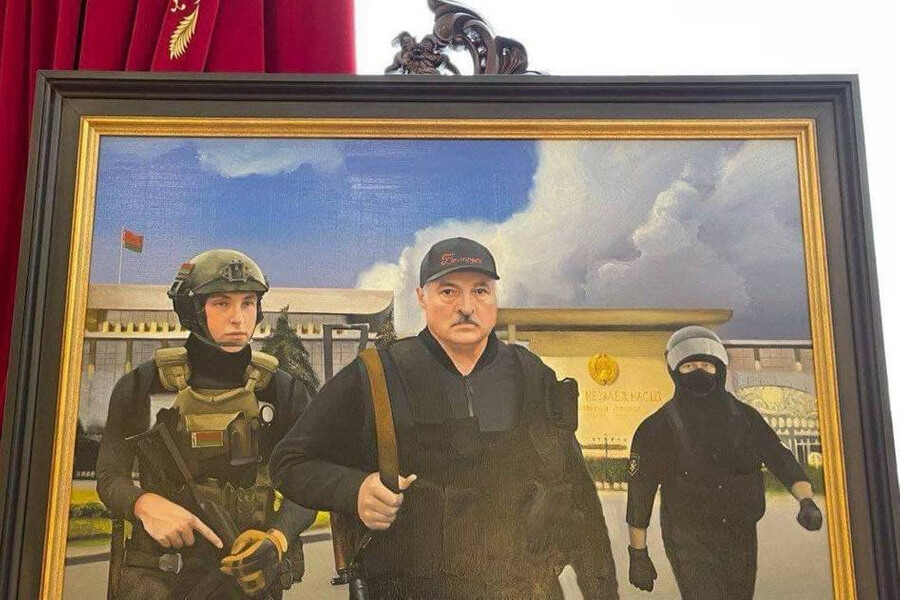

In 2018, state-controlled media journalists presented Łukašenka with his portrait, but anyway the scope of his glorification was not as extensive as in the last two years.

Five years ago, the leaders of Kazakhstan and Russia were already immortalized in quotations, names of cities and streets, and promoted by sophisticated PR stunts.

Everything changed after the 2020 election, which was marred by allegations of massive fraud. Humiliated by strong performance by Śviatłana Cichanoŭskaja, shocked by mass protests and unable to admit the defeat, Łukašenka decided to step up brainwashing.

National idea

To correct the past mistakes, the government launched a campaign of praise as part of a larger strategy to prevent a repeat of the 2020 protests. The cult of personality goes hand in hand with political reprisals and the vilification of the opposition.

As Belarus drifts from authoritarianism to totalitarianism, the halo shines brighter and brighter over the leader’s head.

Another goal of the government’s campaign is to portray Łukašenka as the one who has no alternative. After the 2020 flop, propaganda recasts him as an exceptional statesman who eclipses all others.

In the praise, the regime has finally found its ideological foundations. Officials struggled to invent a national idea before.

In October 2022 Łukašenka said, “It is a short, compact thing that should grab you immediately. You look at it, open your mouth, and you can’t breathe.” And then he sighed helplessly, “I don’t see such an idea yet.”

Officials have finally discovered it: “Alaksandar Łukašenka” is a brief, compact and captivating message.

Interestingly, the ruler no longer speaks out against his own cult. He does not object to public displays of his images. He does not object to the meetings with schoolchildren and students, which have become frequent, or to ecstatic hosannas on television.

No monuments have been erected to him yet, but his own remark from 2021, “Presidents do not become presidents, presidents are born” may indicate that he is ready for one.

Public not responsive to propaganda

A credit to authorities’ ruthlessness, three years after the disputed election a repeat of the 2020 protests looks highly unlikely. However, the cult of Łukašenka has not found a receptive audience.

Fearing repressions, Belarusians may obediently fulfill orders to attend pro-government events, but they would do it through compulsion without enthusiasm.

The heavily-advertised “Merch of the First” has never been popular with Belarusians. Search engines’ analysis suggests that it is mainly intended for export: the merchandize was displayed at an exhibition in Shanghai and offered as a free gift to buyers of Belarusian tractors in Russia. No record sales have been reported, and the chain’s Instagram page was last updated on July 9 last year.

The obsessive cult of personality has a downside: it discourages competition and may prevent Łukašenka, 69, from finding himself a successor.

The examples of Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan and Saparmurat Niyazov in Turkmenistan show that lifelong adulation can end quickly. In Belarus this is especially likely – when the personality falls, the cult will be debunked pretty soon.