One week after warning Poland that Wagner Group mercenaries were eager to “go on a trip” to Rzeszów, Alaksandar Łukašenka said that the Belarus-based fighters are under control, noting that he did not even think of capturing the Suwalki Gap, a land link between Russia’s Kaliningrad and Belarus in the European Union.

During a visit to Biełavežski, Kamianec district, on August 1, the Belarusian ruler reiterated his threats to Poland, mentioning Wagner, nuclear weapons and even the nuclear power plant among his potential tools.

Łukašenka may be scapegoated

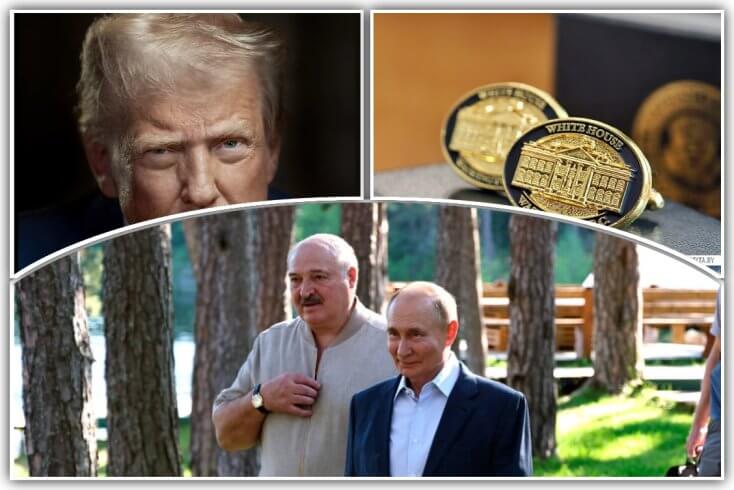

Alaksandar Łukašenka put on a show during his meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in St. Petersburg on July 23, threatening to unleash the Wagner Group on Poland.

He claimed that Wagner militants based in Belarus were eager to carry out incursions into Warsaw and Rzeszów, a hub in southeastern Poland for Western military equipment bound for Ukraine.

Clearly, the Belarusian ruler just tried to amplify Vladimir Putin’s threats to Poland. The Russian president is frustrated with Poland’s support for Ukraine after the February 2022 Russian invasion.

Warsaw responded to the aggressive rant by reaching out to Lithuania and Latvia with the proposal to seal the border with Belarus. The measure would have an immediate economic impact on both sides.

Analysts have warned that Putin might use Wagner mercenaries for hybrid attacks on the European Union (EU), shifting the blame to Łukašenka who allegedly controls the Wagner force now, can supply it with weapons and provide other assistance for possible incursions into neighboring EU countries.

The Belarusian ruler on August 1 denied any malicious plans to assuage those concerns as he tried to emphasize his own political importance.

Who controls Wagner mercenaries?

Łukašenka stressed that he controls the Wagner force stationed in Belarus. He went as far as to suggest that Warsaw should be grateful to him for sheltering the mercenaries.

“Otherwise, without us, they would infiltrate them and kick the shit out of these Rzeszów and Warsaw, they would regret the day they were born.”

Łukašenka seized the opportunity to boast of nuclear weapons’ presence. He said that Russia had already delivered more than half of the planned arsenal to be stored in Belarus.

He touted the Astraviec nuclear power plant as a “very strong security factor.” “If it explodes, God forbid, it will impact them [the NATO neighbors] too.”

In contrast to his July 23 remarks, Łukašenka was more on the defensive than on the offensive. “We don’t encroach on anyone’s backyard, so please stay away from ours.”

Surprisingly, the Belarusian ruler played down threats posed by Poland. “They added 500 men there and 500 here . . . I don’t think they are trying to intimidate us.”

It is hard to reconcile his assessment with anxious statements by Belarusian and Russian generals ostensibly exaggerating NATO’s presence in Poland and criticizing Warsaw’s efforts to secure its eastern flank.

Speaking of Wagner, Łukašenka stressed that he fully controls the mercenaries. “Being stationed in Asipovičy in central Belarus, these guys don’t even think of going anywhere. They have a habit of following orders.”

It is still unclear, however, whose orders they follow now.

Who controls Prigozhin?

In mid-July, Russian MP Andrey Kartapolov suggested that Moscow was sending the Wagner Group mercenaries to Belarus in preparation for an offensive on the Suwałki Gap.

Putin has not yet sorted out all differences with Yevgeny Prigozhin, and the two, most likely, remain at odds. Putin can hardly order the Wagner chief around.

Prigozhin is not interested in gambles such as an insane attack to capture the Suwalki Gap or incursions into Poland. He realizes that his army would be smashed.

Prigozhin is a businessman, not a kamikaze. He might find it more reasonable to keep his force fit for projects in Africa (guarding mines, diamond and gold businesses).

Speaking earlier this month at the Wagner camp in Asipovičy, Prigozhin said that the Wagner contingent would stay in Belarus for a while, training Belarusian troops, and would later travel to Africa.

Łukašenka said that he would like some of the Wagner mercenaries to join the Belarusian Armed Forces to help build a contract army. However, the Belarusian military can hardly afford to pay them the same wages they received as Wagner hirelings.

If the Wagner Group goes on a “trip” into Poland or Lithuania, it would mean that Putin still controls it and pays for it and that Łukašenka is nothing but a servant to the Kremlin.