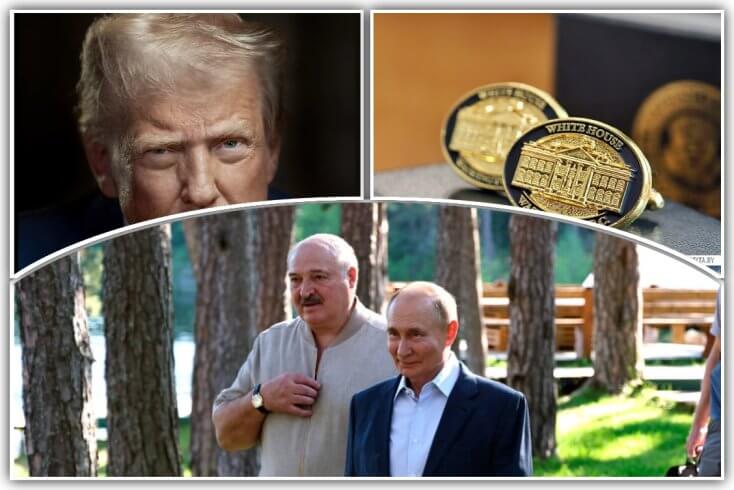

EU officials have sounded alarm over migrants entering illegally through Belarus. A surge similar to the 2021 crisis is considered highly probable. EU politicians point their finger of blame at the Kremlin, assigning AlaksandŁukašenka an important but secondary role.

At the end of May, German broadcasters WDR and NDR, as well as Süddeutsche Zeitung published an investigation into illegal migrants who had entered Germany via Belarus in recent months. Statistics from the German Federal Police show a sharp increase in the spring of 2024.

Arrivals from Belarus via Poland rose from less than 30 in January and February to 670 in April. More than 400 were registered in the first half of May. The numbers were still lower than in 2021.

Migrants come from a wide range of countries, including Sri Lanka, Syria, Eritrea and Somalia.

About half obtained Russian visas in their home countries, and their first destination was either Moscow or St. Petersburg. From Russia, they traveled to Belarus, crossed the Belarusian-Polish border and made their way to Germany.

Western experts stress that illegal migration is part of Russia’s hybrid war against the West. Switzerland’s Watson described migration as the EU’s Achilles’ heel and linked the increased flow of migrants in April and May to the European Parliament election in early June.

Moscow wants far right to strengthen positions in Europe

Immigration has indeed dominated the election, with the Kremlin betting on Euroskeptics, certain far-left and especially far-right parties. The latter have adopted radical anti-immigrant rhetoric and also criticize anti-Russian sanctions and military support for Ukraine. An influx of migrants could strengthen their positions and aggravate the political crisis in Germany.

Has the Moscow’s plan worked? A partial answer to this question can be provided by analyzing performance by the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party that earned plaudits from Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Russian propaganda welcomed the AfD’s success. It came in second nationwide, scoring a convincing victory in eastern Germany, which gave Moscow reason for optimism.

For almost half of AfD voters, migration was the top worry with 95 percent saying that too many foreigners are coming to Germany. Migration was high on the agenda of the new far-left Sarah Wagenknecht Union, which gained just over 6 percent nationally and came in third in eastern Germany.

In September, Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg will hold local elections, in which the far right and far left are hoping to strengthen their positions. The Kremlin will surely be tempted to help these parties, further destabilizing Germany, a key EU country from Putin’s point of view.

Łukašenka’s lobbyists in Germany

An unnamed German security officer told Süddeutsche Zeitung that the migration crisis at the Belarusian-EU border could escalate before the elections in the eastern states of Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia, the states hosting most migrants arriving via the Belarusian route.

The recent death of a Polish soldier, stabbed by an unidentified man as migrants tried to break through from Belarus, might be a harbinger.

In Germany, the media are discussing the AfD’s ties with Moscow. Belarus is also mentioned.

For example, the media attacked Jörg Dornau, an AfD member in the Saxony state parliament, over his agricultural business in Belarus. Die Welt considers Dornau one of the lobbyists of Łukašenka in Germany.

Bundestag member Petr Bystron, accused of working for Kremlin propaganda, is also a member of the AfD. Bystron made a controversial visit to Belarus in November 2022 to meet with then-Foreign Minister Uładzimir Makiej.

Kremlin pulling strings

After the start of the Israeli military operation in the Gaza Strip, Dutch sociologist and migration researcher Ruud Koopmans, along with some other European experts and politicians, expressed fears that the Kremlin would try to flood the EU with Palestinian refugees.

These fears have not yet come true, but one cannot rule out that such plans existed. Their practical implementation may have encountered insurmountable obstacles. Warsaw, Vilnius and Riga have been taking more and more measures to secure their borders and counter subversion by Moscow and Minsk.

Nevertheless, the inflow of migrants is on the rise, and the role of the Łukašenka regime in the current crisis deserves special attention.

Both in 2021 and now, Western media do not consider Minsk as an independent actor, but rather as a puppet of Moscow.

However, there are fundamental differences between 2021 and 2024.

In 2021, Łukašenka acted with Putin’s consent, but he pursued his own personal goal of taking revenge on the EU for sanctions. He hoped that Brussels would ease restrictions and enter in direct negotiations.

Evidence suggests that Minsk organized the illegal migrants’ travel to Belarus and their subsequent transit to the EU. Moscow’s role was limited to a benevolent observer.

The 2021 migration crisis was a failure for Minsk and only increased its isolation.

In the following years, Łukašenka did not stop using migration in his propaganda, but his loose talk has dried down a little recently.

A major escalation would place even a greater strain on Belarus’ already fraught relationship with the EU. This is not in the interests of Minsk, which is still trying to find at least some room for maneuver.

But Łukašenka’s options are extremely limited. Belarus is more dependent on Russia than ever. Moscow is betting on an escalation and imposing its rules on Minsk in all areas, including the migration crisis.

* * *

The danger of further escalation at the border between Belarus and the EU persists. A major crisis would not bring any benefits to Łukašenka, but could only create additional political and economic problems.

The Belarusian government would probably like to avoid it, but it is not in control.